|

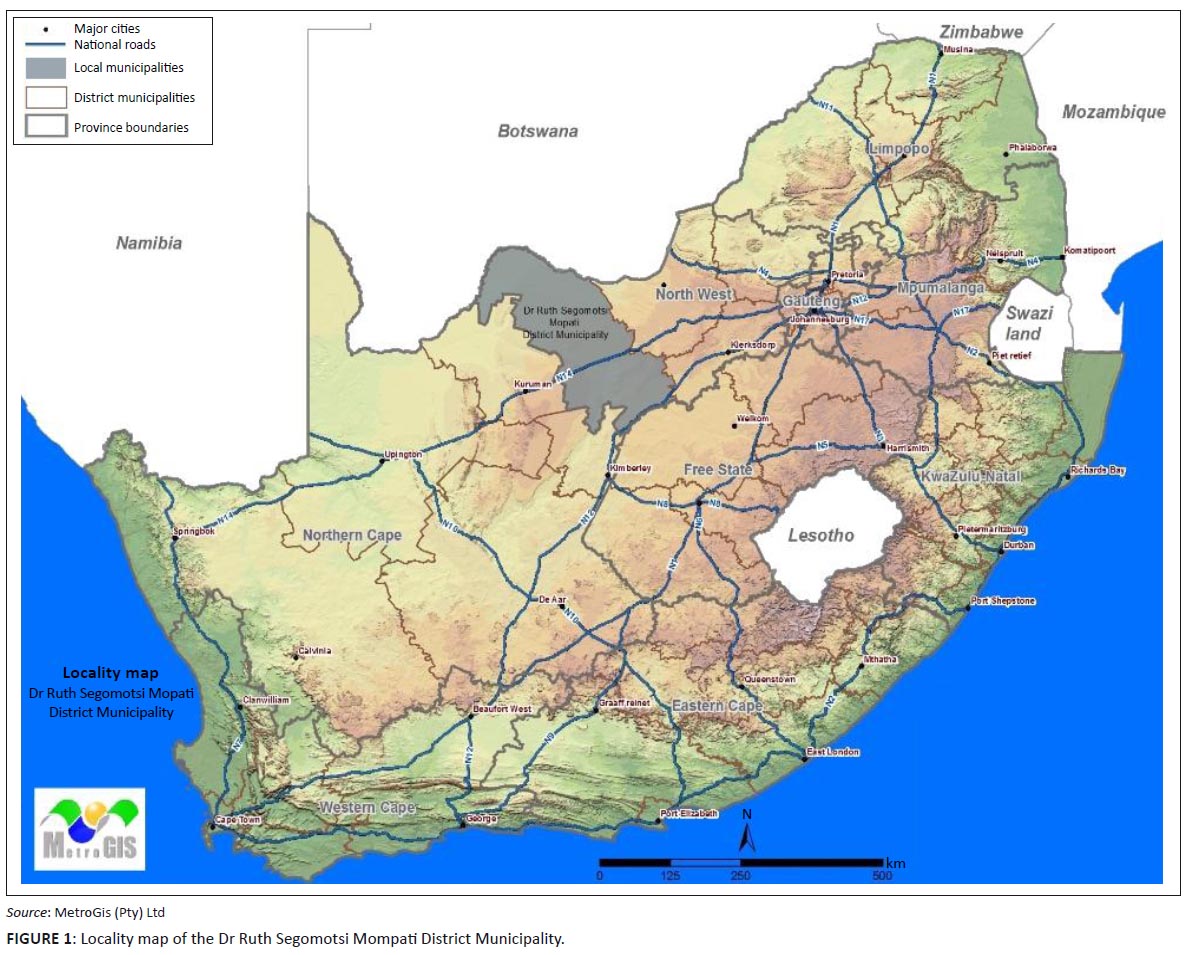

This article adopts an environmental justice approach to recurrent drought in the North-West Province of South Africa. It is based on a secondary data analysis of a study – of which the author was a research team member – conducted in the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality in February 2007, which assessed the impact of drought on older people. The methodology used during the initial study included observation, individual interviews, focus group interviews and participatory research. The author of the present article suggests, however, that discourses of Disaster Risk Management (DRM) and ’legislative compliance’, as in many other South African contexts, have not yet been a particularly useful framing for issues of disaster and drought. The author suggests that environmental justice discourses might offer a more useful framing or conceptualisation

for those concerned with the issue of recurrent drought in the study area or similar contexts.

The Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality in the North West Province of South Africa is a drought-prone area. Livelihood activities in the region mostly revolve around communal and commercial cattle farming. In light of the dualist, historically racially determined manner in which South African agriculture is organised, commercial and subsistence farmers bear an unequal share the effects of recurrent drought, and by logical extension, potentially adverse climatic changes. In this paper, the author assesses this issue of recurrent drought in the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality, from the perspective of environmental justice. The argument is structured as follows: firstly, a literature review is presented regarding issues of poverty, inequality and agriculture in South Africa and how it pertains to discourses of environmental justice. This is followed with a discussion of the study area and the research methodology employed. Thereafter, the author discusses the various effects of drought on the research area and the challenges faced regarding people’s capacity for coping with drought. The paper focuses in particular on discourses of ’disaster risk management’ and ’legislative compliance’ and the political legacy accompanying the impacts of drought. The paper concludes by suggesting that, as regards the issue of recurrent drought in South Africa, environmental justice discourses might provide an apt and more useful alternative, or at least a supplement, to (poorly) institutionalised ’risk management’ structures and practices.

|

Rural inequality and environmental justice in South Africa

|

|

South Africa is a middle-income country with a significant degree of income inequality. In fact, it has one of the most unequal populations in the world, judging from the often-cited Gini-coefficient.1 According to the United Nations Development Programme (2008), South Africa has a Gini coefficient of 0.57, the fifth highest in the world. This inequality is evident in the make–up of the South African agricultural sector, historically determined as comprising mostly White commercial farmers and Black subsistence farmers, the latter living in former homeland areas.2 Subsistence farmers often rely on state grants, mostly pensions, as a major additional income source (Vetter 2009:32). South Africa is primarily a semi-arid country that experiences significant rainfall variability in the form of droughts, floods and storms (Vogel 2009:86). Drought is a recurrent hazard in various parts of the country, especially in the northern summer-rainfall areas (Reason & Phaladi 2005:544), and in addition to causing crop failures and loss of employment, compounds other stressors, such as low, income levels and food insecurity (Pelser 2001:59). Drought also compounds processes of environmental degradation, which has long been a concern in former homeland areas. With the adoption of the 1913 Land Act, only 13% of land was reserved for Black South Africans. This form of segregation was further formalised with the ’independence’ of many of these areas as ‘homelands’. Environmental degradation essentially resulted because of overcrowding. The result is therefore that many rural citizens now depend on what Pelser (2001:62) describes as a ’fast degrading environment’, a situation exacerbated by the position of smallholder farmers in all developing countries, namely, lack of access to credit as banks do not consider them creditworthy (Vogel 2009:92). Climate change is seemingly an additional emergent stressor, which further compounds the issue of drought. Even though there still seems to be some variation in the estimations, there does seem to be a level of consensus as regards the likely adverse effects on rainfall. In particular, according to Mukheibir & Ziervogel (2007:143), there will be a likely increase in rainfall variability in southern Africa. This climatic change could exacerbate existing inequalities in rural areas, highlighted above. Inequality in South Africa is to a significant extent shaped by a very high level of unemployment, which in turn results from forces extending beyond the national level of analysis. Situated in the world economy, the country, like all others, is currently subject to conditions of neoliberal governmentality (Bondi 2005, following Foucault) or neoliberal hegemony (following Gramsci). What this means is that numerous political and economic discourses are continuously being shaped by the broader meta-narrative of neoliberalism, with accompanying elements such as the retreat of the state from the economy in various shapes and forms. One clear manner in which such factors impact on agriculture is seen in the decrease in agricultural subsidies in the 1990s, which led to significant job losses on commercial farms, although, granted, mechanisation also played a role (Seekings & Nattrass 2005). White commercial farmers enjoyed much support in the form of subsidies during apartheid. With democracy this changed, to the extent that many commercial farmers have prematurely ’retired’, changing occupations. Another area in which this neoliberal governmentality is influencing the South African landscape is through disaster risk assessment and management. In accordance with discourses of ’New Public Management’, much of disaster risk management (DRM) has been outsourced. In other words, as van Riet and van Niekerk (2012) note, DRM seems to be something that is done every few years at municipal level, by consultants, typically in the form of drafting disaster risk assessments and disaster risk management plans, in order to achieve ’legislative compliance’. The result has been that the institutionalisation of DRM in South Africa has been significantly lacking in terms of legal specifications. Botha

et al. (2011) and van Riet and Diedericks (2010) find that most municipalities lack the most basic of prescribed disaster risk management structures. The argument in the current article is therefore that discourses such as ’environmental justice’, which is necessarily accompanied by practices of protest politics, might be a useful addition to technical risk assessment and management discourses, which have as yet, not significantly delivered on their initial promise. Environmental justice refers broadly to a combination of ’green’ and social justice issues, often referred to as ’brown issues’ (e.g. Cock 2003). This discourse for example refers to such cases as hazardous industries erected next to impoverished settlements as opposed to wealthy communities. It also pertains to equitable access to natural resources in rural areas. Environmental justice emerged in North-America in the 1980s under minority groups, in response to polluting industries for the most part located in their neighbourhoods. Non-minority groups it seems had sufficient power to articulate, ‘Not in my backyard’ (NIMBY) in some form or another. This agenda gradually penetrated other parts of the world, notably South Africa. Since the early 1990s, environmental justice has served as a key discourse around which communities and civil society organisations have mobilised in South Africa, for example under the ambit of the Environmental Justice Community Networking Forum (EJNF) as a loose umbrella organisation formed in 1992, which at its peak comprised more than 550 organisations. This pressure group, especially, has served as a major vehicle for successful community protests around the country (MacDonald et al. 2002). Its influence in the 21st century, however, has been far less (Leonard & Pelling 2010). Section 24 of the 1996 Constitution (SA 1996) includes a clause stating, to paraphrase, that every South African has the right to a safe, healthy, and sustainable environment. However, in practice the forces of modernity have made it very difficult to add any substance to such rights. Ensuring what Amartya Sen (1999) calls ’substantive freedoms’, as opposed to purely formal freedoms, in the South African context has in effect been very difficult. In light of this, protests and other forms of mobilisation, which fall outside of the traditional liberal democratic processes, might be particularly useful in providing a voice to marginalised groups. These protests have not been forthcoming in rural areas to any significant extent, however, even though, in a rural context, the issues of land reform and environmental degradation are particularly germane to that of environmental justice, as it relates to fair access to natural resources.

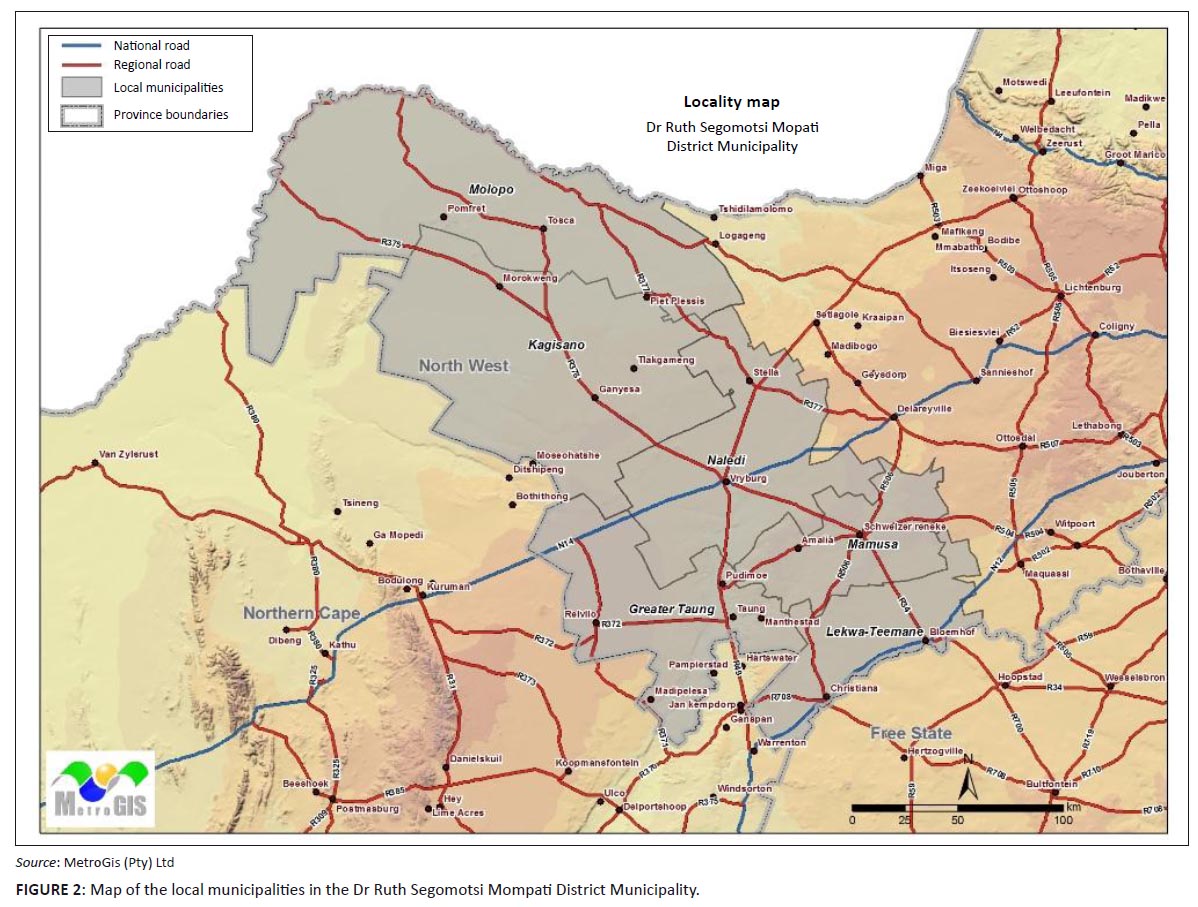

The Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality is located in the North-West Province of South Africa, with the Botswana border immediately to the north. This area, commonly known as the ’Texas of South Africa’, is characterised by cattle farming as the most significant economic activity. The study area is furthermore characterised by a particular political legacy. A portion of the Municipality is located in the area of the former Bophuthatswana, which served as a homeland for the ‘Tswana ethnic group’.3 Homelands such as Bophuthatswana also used to serve as labour reserves for South Africa. Thus, even though South Africa granted these entities ‘independence’, they were inextricably linked to the South African economy in an exploitative manner. In fact, one can still view a particular dualism regarding agricultural practices. The area is made up by mostly White-owned commercial farms and by Black communal or subsistence farmers, typically farming on land that is officially state owned.In accordance with the manner in which South African local state structures are organised, the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality is divided into smaller administrative units (see Figure 2). These are the Molopo (MLM), Greater Taung, Naledi, Mamusa, Lekwa-Teemane and Kagisano (KLM) local municipalities. The research team conducted fieldwork in the towns of Tosca and Ganyesa in the MLM and KLM respectively. Since the research, these two local municipalities have been collapsed into one local municipality. The distinction is kept, however, to better orientate the reader, as the research was undertaken whilst these were still separate administrative units.

Data were collected during fieldwork for a Help the Aged/World Health Organization-commissioned case study on the impact of drought on older

people (van Niekerk et al. 2007). The majority of participants interviewed were above the age of 60. The fieldwork revealed that a large proportion of the farmers in the study area fitted into this age category. Older persons are therefore reliable informants regarding agricultural practices in the area, as they are sufficiently representative of farmers in the study area. They also carry substantial knowledge of the area, beyond their own, personal experiences. The researchers made use of purposive sampling of older people. In this regard, the assistance of a local Non-governmental organisation (NGO) in organising. NGO in organising interviews and thus serving as a gatekeeper was helpful. The fieldwork phase entailed individual interviews, focus group interviews and group interviews using the Mmogo method (Roos 2008). The Mmogo method encompasses the use of ’culturally appropriate artefacts’ (or perhaps better stated as contextually appropriate) in order to create objects symbolising behaviour between participants and their relationship with their environment.4 Accordingly, researchers asked participants to build models indicating their experience of drought. After completing these visual representations, participants were asked to explain their meaning. In total, the researchers conducted individual interviews with four farmers and seven state officials. In addition, they facilitated seven group discussions, comprising 37 participants in all. Three of these group interviews made use of the Mmogo method, whilst the other four were more conventional focus groups. Focus group participants included one group made up of White commercial farmers older than 60, one group made up of Black commercial farmers older than 60, one group of Black community residents above the age of 60, colloquially referred to as ’elders’, one group of state officials and finally two groups of community residents under the age of 60. Therefore, the sample still represented younger community residents (van Niekerk et al. 2007:20). Researchers assured participants of confidentiality, in order to facilitate open and honest discussion. Researchers typically initiated interviews with a very broad general question, such as: ’Please tell me how you have experienced drought?’ Where and when required, this was followed with more specific probing questions. The researchers initially conducted thematic analysis on the data for the purposes of the above stated report, based on Bronfenbrenner’s General Systems Theory (van Niekerk et al. 2007:24−25). The report culminated in certain policy recommendations to municipal officials and politicians (van Niekerk et al. 2007:51). These recommendations pertained to such issues as the implementation of legislation, employing more disaster management staff, awareness campaigns and other more general issues, such as generating additional livelihood activities. The authors, of course, in the context of that particular study, specifically related many of these issues to the needs of older people. For the purposes of the current article, the author reinterpreted the data from an environmental justice perspective, in an attempt to explore intellectual spaces beyond the confines of existing legislation.

|

FIGURE 1:

The study area (Glefe) located in the Densu wetland area.

|

|

|

FIGURE 2:

Map of the local municipalities in the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality.

|

|

|

The impact of recurrent drought in the study area

|

|

By far the most significant livelihood activity in the study area is cattle farming, which is by nature a rain-fed agricultural activity. Very few commercial or subsistence farmers can afford irrigation, under which those who do have it, often plant crops. Residents in the area are typically older people. Younger, especially Black residents, tend to move to urban areas in order to find alternative employment opportunities. In the case of Black families, older residents then typically look after their grandchildren, and eke out a living through subsistence agriculture and often receive state grants, such as pensions or childcare grants.By the participants’ estimations, drought in study area on average occurs every 20 years. However, droughts have become more frequent and their frequency more unpredictable over recent decades (Hudson 2002:23). Participants suggested that climate change might have already begun affecting the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality. They stated that they could recall the occurrence of regular and long-lasting droughts since the 1920s, but that the frequency and duration of droughts appears to be increasing. One district official noted: ’The normal times of rain has changed’. Rains often occur later in the season. The impact of drought in the area over time has been far reaching, resulting in a loss of grazing land, which typically translates into a loss of cattle. Participants indicated that they had lost up to 80% of their cattle in one particular drought. Furthermore, drought often leads to other disasters, for example, veld fires and the spread of animal diseases. In addition, stock theft often occurs during times of drought. Finally, owing to the quality of stock typically available in a drought-stricken area, stock prices often fall.

|

Drought-coping mechanisms

|

|

The notion that communities are destined to victimhood with regard to natural disasters has arguably become archaic. The movement in Development Studies since the 1980s, focusing on the capabilities of communities, is evidence of this (see Chambers and Conway 1991 & Sen, 1999). In such a drought-prone area, one may expect that coping mechanisms are significantly evolved. Indeed, the data confirmed that the communities investigated usually had some capacity to cope with natural hazards. The most common coping mechanism reported, especially by commercial farmers, was selling older cattle in order to buy feed for the younger, stronger cattle. Some participants indicated that they undertook basic water harvesting through catching and saving water in baskets, pots and bowls, in order to be prepared for times of drought. Other participants indicated that they made use of traditional knowledge as a drought-coping mechanism, for example cutting down a Motopi tree, grinding it and feeding it to their cattle or consulting the lunar cycle and stars in order to determine seasonal patterns. Other strategies reported include eradicating foreign shrubs, taking water to the cattle instead of making them walk long distances, keeping cattle clean and rotating grazing fields. One state official noted that the latter practice was still not widespread, leading to environmental degradation. However, one may easily explain this by drawing on a political economic mode of analysis, rather than simply ascribing it to ignorance on the part of farmers. As Hudson (2002) states, field rotation directly relates to the availability of boreholes. Commercial (also read historically advantaged and more wealthy) farmers typically have many more boreholes on their farms, making it easier to provide cattle with drinking water in various camps. Communal farms often have only one or two boreholes, making this much more difficult. This generally results in land degradation around existing watering points. Some of the commercial farmers interviewed noted that they had installed irrigation on their lands after many years of struggling with drought and their situation subsequently improved. They did; however, also note that other commercial farmers had completely given up farming and moved away from the area. In addition to the drought-coping mechanisms noted above, participants reported mechanisms considered in this article as coping mechanisms yet not considered as such by the participants. These include savings schemes, burial societies and permission obtained by traditional leaders from neighbouring chiefs for temporary grazing rights.5 Despite these drought-coping mechanisms, many communal farmers felt that they could do little to cope with drought. One participant stated, ’People are sitting here and doing nothing, because of no money and hunger’. Other communal farmers indicated that they ’prayed for rain’ or ’waited for rain’. There appears to be significant dependence by subsistence farmers on state old-age pensions. This corresponds with findings of previous studies conducted in various parts of South Africa, where up to three generations depend on one state grant (Case & Deaton 1998; Duflo 2003). The participants indicated that dependence on these grants increased in times of drought.

|

Challenges regarding drought-coping capacity

|

|

This section covers two broad themes pertaining to drought-coping capacity in the study area: discourses of disaster risk management and the political legacy associated with recurrent droughts in the region. The former is associated with very narrow interpretations of ’legislative compliance’. With the latter,

the author attempts to bring historical and material disparities back into the picture.

The genesis and nature of the discourse of disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management should not be new to the readership of Jàmbá. Readers might not; however, be that familiar with the particular South African legislative context, legislation that has obvious implications for drought-coping capacity in the study area. The South African Disaster Management Act (DMA [SA, 2002]) and the National Disaster Management Framework (NDMF [SA 2005]), which serves as a guideline for the implementation of the Act, place certain obligations on local and district municipalities. These obligations include creating structures such as disaster management centres, and employing staff dedicated to disaster management. As an example, for the sake of ’mainstreaming’ Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) into development, the legislation requires that interdepartmental committees are established in all local and district municipalities, chaired by the head of the disaster management centre and consisting of members of all municipal departments. This, the argument goes, would ensure that the often-cited multidisciplinary nature of DRM is honoured. Such committees serve as decision-making bodies for matters relating to disaster management in their jurisdiction. In addition, all municipal departments are to incorporate DRR into their daily duties. The DMA therefore defines disaster risk management (DRM) as a continuous and integrated, multi-sectoral, multidisciplinary activity (SA 2002). Following from these legislative requirements, previous research (van Riet & Diedericks 2010; Botha et al. 2011) investigated questions around whether and how such interpretations of legislative compliance have in fact been realised – focussing on whether structures and institutions are in place. The resulting findings were, typically, distinctly negative. The data that the current article is based on also indicate many shortcomings, both at local and district municipal levels. Institutional structures were not found to be in place. In addition, local government did not possess disaster risk assessment reports and/or risk management plans, local and district municipality disaster management structures were understaffed and local and district municipalities were seemingly unable to coordinate risk management activities between them. In particular, communication between local and district municipal level appeared to be very poor, something that was mentioned by almost every official we spoke to. At the time of the study, the district employed only two functionaries dedicated to DRM. Although the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality has a disaster management centre, the head of the centre holds three other portfolios. For such a disaster-prone area (recurrent drought is but one frequent hazardous event), the centre seemed to be understaffed. In terms of legislative requirements, the district’s disaster management plan complied with the DMA. However, at the time of the research, it did not comply with the NDMF, as the plan was developed before the framework’s inception and has not been updated since.6 It therefore appeared that the various district municipal structures, again perhaps unsurprisingly, did not hold disaster risk management in much regard. Further evidence of this includes ’insignificant buy-in’ on the part of politicians regarding DRM, something noted by most officials we spoke to. At local, as opposed to district municipal level, staff capacity seemed an even greater concern. In the MLM, one senior administrator ’attended (DRM) meetings in the district’. The KLM did not have a dedicated functionary for DRM, in any form. The local municipalities appeared to believe that as DRM is officially the responsibility of district municipalities, local municipalities have very little or no role to play. This is further evidenced by the fact that local municipal officials mentioned very little in terms of proactive measures to mitigate the impact of drought in the area. Staffing disaster management structures of course has no value in and of itself. If mitigation is to be ’mainstreamed’ into development, (Mitchell 2003; Benson & Twigg 2007), then the South African legislation is clear, in that disaster management centres fulfil a key function by integrating and coordinating the activities of various departments. However, this is clearly problematic in contexts where municipalities are so poorly resourced. Under the conditions discussed here, it seems a very ’tall order’ to expect understaffed bureaucracies to fulfil such a mammoth undertaking. In this sense, the argument by South African political scientist Robert Cameron (cited in Cameron & Thornhill, 2007) seems relevant. He argues that ’issues of policy implementation’ are actually often issues of policy. What he means is that policy makers are often overambitious and out of touch with realities on the ground as regards the potential for policy implementation. Therefore, one needs to start questioning the usefulness of empirical investigations into the state of DRM ’legislative compliance’ in South Africa, be it in terms of structures, risk assessments and risk management plans. If we move away for a moment from the specific context of the study area, we might feasibly raise a more general concern. Perhaps this technicist, ’expert’-driven approach, rooted in the broader context of neoliberal governmentality, whereby consultants are employed in order achieve a very narrow definition of ’legislative compliance’, typically in the form of expert reports, is not particularly useful. At the very least, it should perhaps be supplemented with something else. Stated differently, how useful is it to merely produce consultants’ reports every few years, when not much else is done as regards prevalent dangers, and where DMCs are not capable of ’coordinating risk management activities’? With this in mind, the paper now turns to another line of questioning and/or probing that the research team followed when interviewing officials, farmers and other residents. In addition to asking what formal ’risk management’ structures and documents were in place, we also enquired as to what other actions the state and residents employed that one might construe as facilitating risk reduction. These findings, although slightly more promising, are still disappointing, lending further credence to my suggestion that appropriate civil society members should supplement formal top-down measures with pressure on the state, drawing on such discourses as environmental justice. Whilst certain local government departments did reveal existing mitigation activities, these activities assist only a small minority of the

communities. The activities in Tosca included a community hydroponics project, a community bakery, rainwater harvesting and the drilling of boreholes (unfortunately, many of these had already dried up). In Ganyesa, the local authorities had undertaken a food security programme in the form of poultry keeping, piggeries and food plots. The Department of Agriculture in Ganyesa provided training regarding coping with drought and made drought-coping information available at their offices. There were two problems regarding this, however, firstly, illiterate community members could not access this written information, and secondly, many community members only learnt of the training after its completion. When asked about drought mitigation initiatives in the area, one Department of Social Development official noted: ‘You do not bring a project to people who did not initiate it, because you will be spending money for nothing. It is better for people to have the initiative and then we bring the funding to them.’ (Participant A, Department of Social Development official) Although there may be merit in such an observation – discourses of local ’ownership’ are quite common in more recent development debates – such an attitude on the part of local government might not be very useful. Community ownership surely does not necessarily mean that initiatives should originate from the community (of course, bearing in mind that state or non-state actors do not force inappropriate projects onto communities). What this section has thus indicated is that, although discourses of risk reduction, risk management and ’legislative compliance’ (counting structures) are prevalent, implementation in the study area has been slow, at best. However, drought mitigation efforts, in any form, therefore, – to extend the concept further – were also found to be very limited. Up to this point, the paper has made a partial case for why a greater sense of urgency is required regarding the uneven impact of recurrent drought in the study area. The argument now moves on to the matter of political legacy and the historically-rooted nature of suffering under recurrent drought. The discussion below should consequently strengthen my argument and make it clear why one might usefully construe the matter of recurrent drought in the area as an environmental justice issue.

The dual system of White commercial and Black subsistence farming coexisting side by side has implications for livelihoods in regions such as the study area. This matter of political legacy therefore relates to issues such as the ability of farmers to cope with recurrent drought, land reform and historical racial antagonisms, as well as – the author wishes to argue – the historical denial of environmental justice for many. By way of linking with literature referred to above on environmental degradation in former homeland areas, one might note that grassland degradation is a substantial problem in large sections of the study area. According to Hudson (2002:33), who researched roughly the same area, communal farmers have a higher stocking rate (amount of animals per unit area) than commercial farmers do and are thus more susceptible to drought. Moreover, communal farmers are far more reluctant than commercial farmers are to sell cattle in times of drought (Hudson 2002:33). Overgrazing is thus of concern, particularly in areas in which water sources are not sufficiently spread out. This is not because communal farmers are unwilling or unable to conduct respectable farming practices (often read in terms of persistent modernisation logic). Simply put, there are structural constraints disrupting existing agricultural practices, which are largely a result of western imposition. Stated differently, one need not look much further than the Land Act of 1913 and the subsequent homeland policy (although the matter can arguably be taken back even further), to see that many South Africans have been constrained in terms of access to land and resources, not at all by their own doing. Furthermore, communal farmers in Ganyesa were concerned regarding land tenure. They had no contract with the state and were therefore not certain that they would reap the benefits of their labour (van Niekerk et al. 200:43). In fact, some of the communal farmers felt that the best agricultural land was still in the hands of White, commercial farmers. As stated above, South Africa has one of the highest levels of inequality in the world regarding wealth distribution. Although wealth inequality in South Africa currently crosses intra-racial boundaries, the inequality in the study area tends to follow racial lines, with commercial agriculture overwhelmingly residing in the hands of White farmers. Of course, land reform (where residents desire this) is an obvious way in which to potentially affect improved equality in areas such as the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality, where agriculture is by far the most important livelihood activity. At the time of the research, the state had earmarked certain farms for redistribution. However, if recipients fail on land that is not suitable for agriculture, or only marginally suitable, then the land reform programmes will not meet their political and economic objectives. This issue is significant. As noted above, some commercial farmers have ceased farming in the area, owing to the harshness of conditions. Under such conditions, land transferred from White commercial farmers to Black farmers needs to be sufficiently suitable for agriculture. Still, this issue is hardly a viable counter-argument to land reform. In fact, the evidence also suggests significant disparity between the ability to cope with drought and the level of environmental degradation that commercial and especially communal farmers experience. Therefore, by considering the issue of recurrent drought in the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality as an environmental justice issue, one can better emphasise the political historical context of the subject. This is one potential alternative or supplementary conception of drought-related phenomena to technical risk assessment and management discourses. Such a perspective or perspectives, would have to view this and similar areas as part of the broader South African economy. To be sure, issues of rural and urban development are dependent on one another. For example, interventions, in rural areas might affect patterns of urbanisation, whilst the opposite is also true. Furthermore, issues such as rural land reform and alternative income generating activities in areas such as the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality are of national significance. Citizens or civil society organisations might find ’alliances’ in other parts of the country. Regarding these alliances or solidarity around particular discourses, such as environmental justice, my earlier analysis seems to suggest that the study area might require significant ’bridging’ and ’linking’ ties to other geographical areas (Leonard & Pelling 2010:141). The residents of the study area have not yet, to my knowledge, mobilised around environmental justice or other similar discourses. Thus, ’bridging ties’ (across a similar cross section of society) and ’linking ties’ (vertical ties across, for example, social classes) might be required.

It seems that discourses of disaster risk assessment and management have not yet proven significantly useful regarding the problem of recurrent drought in the Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati District Municipality. By considering the historically determined political economic context of this recurring problem, analyses and other actions might develop a greater sense of urgency. Discourses of DRM and legislative compliance might serve as something around which to mobilise, although clearly, depending on the state and the private sector to drive ’DRM’ has not yielded significant results across South Africa. Perhaps greater pressure from various civil society members might be a more useful avenue to pursue. In this regard, drawing on and rallying around environmental justice discourses might produce a range of logical allies, whilst the issue of environmental justice also seems an appropriate conceptual fit, given the historical, political and economic context of drought in the area. There is already some evidence of the success of this movement in urban areas, although this might change. Cornwall and Eade’s (2010) edited volume Deconstructing development discourse: Buzz words and fuzz words, which is a collection of essays on various development concepts, suggests that as discourses become institutionalised and applied in various contexts, they often become fuzzy, or malleable and devoid of significant substance. The same might also happen to ’environmental justice’. The author’s approach is pragmatic, however, taking the reported success of environmental justice-based movements in the past and the emotive appeal of notions of ’justice’ as indicative of the promise such approaches hold, at least in the shorter term.

Competing interest

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Adger, W.N., Huq, S., Brown, K., Conway, D. & Hulme, M., 2003, ‘Adaptation to climate change in the developing world’, Progress in Development Studies 3(3), 179−195, n.d., from http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1464993403ps060oaBenson, C. & Twigg, J., 2007, ‘Tools for mainstreaming disaster risk reduction: Guidance notes for development organisations’, viewed 30 October 2009, from

http://www.livestock-emergency.net/userfiles/file/common-standards/Benson-Twigg-2007.pdf Bondi, L., 2005, ‘Working the Spaces of Neoliberal Subjectivity: Psychotherapeutic Technologies, Professionalisation and Counselling, in R. Cameron & C. Thornhill (eds.), 2009, Antipode, pp. 497−514, Journal of Public Administration 44(4.1), 897−909. Botha, D., Van Niekerk, D., Wentink, G., Coetzee, C., Forbes-Biggs, K, Maartens, Y., et al., 2011, ‘Disaster Risk Management Status Assessment at Municipalities in South Africa’, Report to the South Africa Local Government Association (SALGA), viewed 24 August 2011, from

http://www.acds.co.za Case, A. & Deaton, A., 1998, ‘Large cash transfers to the elderly in South Africa’, Economic Journal 108(450), 1330−1361, viewed 05 June 2012, from

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00345 Chambers, R. & Conway, G.R., 1992, ‘Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the twenty-first century’, IDS Discussion Paper 296, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. Cock, J., 2004, ‘Connecting the red, brown and green: The environmental justice movement in South Africa’. Research report (Centre for Civil Society/Centre for Development Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, viewed 23 January 2012, from

http://ccs.ukzn.ac.za/files/CockonnectingtheredbrownandgreenTheenvironmentaljusticemovementinSouthAfrica.pdf Cornwall, A. & Eade, D. (eds.), 2010, Deconstructing development discourse: Buzzwords and fuzzwords, Practical Action, Oxford, Rugby, Warwickshire, UK. Duflo, E., 2003, ‘Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intra-household allocation in South Africa’, World Bank Economic Review 17(1), 1−25, viewed 06 June 2012, from

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhg013 Foucault, M., 2010, The government of the self and others − Lectures at the Collège De France, transl. G. Burchell, Palgrave Macmillan, New York. Gramsci, A., 1999, Selections from the prison notebooks, vol. 1, transl. Q. Hoare, G.N. Smith (eds.), The Electric Book Publishing Company, London. Hudson, J.W., 2002, Responses to climate variability of the livestock sector in the North-West Province, South Africa, M.A. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, viewed 28 October 2009, from

http://digitool.library.colostate.edu///exlibris/dtl/d3_1/apache_media/2295.pdf International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2007, ‘Summary for policymakers’, in M.L. Parry, O.F., Canziani, J.P., Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, C.E., Hanson (eds.), Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability − Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth assessment report of the International Panel on Climate Change, pp. 7−22, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, viewed 27 October 2009, from

http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg2/ar4-wg2-spm.pdf Leonard, L. & Pelling, M., 2010, ‘Mobilization and protest: environmental justice in Durban, South Africa’, Local Environment 15(2), 137−151.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13549830903527654 Macdonald, D.A. (ed.), 2002, Environmental Justice in South Africa, University of Cape Town Press, Cape Town. Mitchell, T., 2003, ‘An operational framework for mainstreaming disaster risk reduction, Benfield Hazard Research Centre Disaster Studies Working Paper 8’, viewed 28 October 2009, from

http://www.abuhrc.org/Publications/WorkingPaper8.pdf Mukheibir, P. & Ziervogel, G., 2007, ‘Developing a Municipal Adaptation Plan (MAP) for climate change: The city of Cape Town’, International Institute for Environment and Development 19(1), 143−158. Pelser, A.J., 2001, ‘Socio-cultural strategies in mitigating drought impacts and water scarcity in developing nations’, South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 30, 52−74. Reason, C.J.C. & Phaladi, R.F., 2005, ‘Evolution of the 2002−2004 drought over northern South Africa and potential forcing mechanisms’, South African Journal of Science 101, 544−546, November/December. Reid, P. & Vogel, C.H., 2006, ‘Living and responding to multiple stressors in South Africa: Glimpses from KwaZulu-Natal’, Global Environmental Change 16(2), 195−206.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.01.003 Roos, V., 2008, ‘The Mmogo-method: Discovering symbolic community interactions’, Journal of Psychology in Africa 18(4), 659−668. Seekings, J. & Nattrass, N., 2005, Class, Race and Inequality in South Africa, Yale University Press, New Haven. Sen, A., 1999, Development as freedom, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. South Africa, 1996, Constitution Act 108 of 1996, State Printer, Pretoria. South Africa, 2002, Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002, State Printer, Pretoria. South Africa, 2005, National Disaster Management Framework, State Printer, Pretoria. United Nations Development Programme, 2008, ‘Human development report 2009’, viewed 30 October 2009, from http://hdrstats.undp.org/indicators/147.html Vetter, S., 2009, ‘Drought, change and resilience in South Africa’s arid and semi-arid rangelands’, South African Journal of Science 105, 29−33, January/February. Vogel, C.H., 2009, ‘Business and climate change: Initial explorations in South Africa’, Climate and Development 1(1), 82−97, viewed from

http://dx.doi.org/10.3763/cdev.2009.0007 Van Niekerk, D., Roos, V., Van Riet, G., Gerber, O., Combrink, I., Chigesa, S., et al., 2007, ‘Research into ageing: The impact of drought in the Bophirima District Municipality (South Africa) on older people’, Report to Help the Aged, African Centre for Disaster Studies/Dept. of Psychology, North-West University, Potchefstroom. Van Riet, G. & Diedericks, M., 2010, ‘The Location of Disaster Management Centres at Provincial, District municipal government in South Africa’, Administration Publica 18(4), 155−173. Van Riet, G. & Van Niekerk, D., 2012, Capacity development for participatory disaster risk assessment − Environmental Hazards: Human and Policy Dimensions, viewed from

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/showAxaArticles?journalCode=tenh20

1.The Gini coefficient is a measure of dispersion used to measure inequality of wealth. A score of 0 indicates perfect equality and a score of 1 indicates perfect inequality.2.The apartheid state created homelands as independent ‘states’, serving as cheap labour reserves to ‘White South Africa’. This system gave all Black people ‘citizenship’ of the homelands. In this sense, the South African state promoted the institutionalised racism that was apartheid as a policy of ‘good neighbourliness’. Bar the apartheid state, however, all other states refused to recognise the independence of these homelands.

3.This term is placed in inverted commas, as it might be taken to imply ’ethnicities’ as bounded units, as opposed to being fluid, malleable, historically constructed and often instrumentalised for political gain.

4.Again, ’culturally appropriate’ might be construed as referring to bounded or distinct ’cultures’. I therefore replace the phrase with ’context’ designating a particular time and space. 5.A burial society is an, often informal, group savings scheme in a particular area or ’community’. Members make monthly contributions towards a fund, drawn from when a family member passes away. Burial societies may also offer non-material support in the event of a member’s relative passing on.

6.The NDMF is a separate document to the DMA. It elaborates on various key aspects of the DMA and serves as a guide for its implementation.

|